For Instructional Improvement, Address the Knowing-Doing Gap Represented In Instructional Continuums

January 24, 2023 January 24, 2023

If learning can be thought of as a continuum or an ongoing journey to improve, adapt, and grow, then so must instruction. After all, instructional improvement, or effective instruction, is largely an outcome of a teacher’s understanding and use of specific strategies, skills, and structures – each ranging in its use and effectiveness. It is this range that constitutes an instructional continuum.

We prove the existence of these continuums every time we try something new. Whether it goes well or it flops, there are always specific behaviors we did or did not do that contributed to the outcome. It is these behaviors that make up the progression of a continuum.

What Is the Knowing-Doing Gap in Education?

If we fail to recognize how changing behaviors can change outcomes, or if we understand change is needed, but are unsure how to go about it, then we can become “stuck” in our current instructional practices. We can also call this a Knowing-Doing Gap. This gap exists within every instructional continuum. The Knowing-Doing Gap is the divide between what we know, what we think we know, and what we do on a consistent basis.

The Knowing Gap

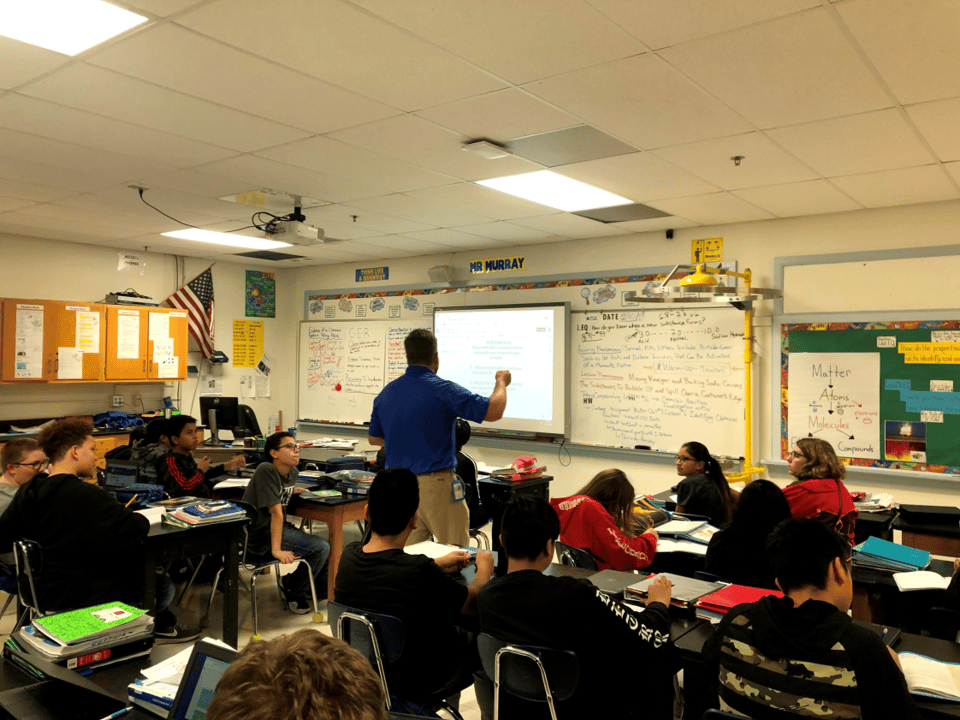

Each continuum begins with an educator’s knowledge of the strategy, skill, or structure in question, and progresses to their ability to adaptively use it to address a variety of student learning needs. What I have frequently observed when visiting classrooms, is that differences in implementation have little to do the number of years of experience a teacher has (at least after the initial learning curve of on-the-job training experienced by new teachers during their first few years in the classroom), or even the content area or grade level of the class.

Instead, it is a teacher’s understanding of the best possible use of the strategy, skill, or structure, and their consistent self-assessment of their use of it, that makes the greatest difference in its implementation and students’ success. Why? Depending on where a teacher is on a continuum, they may not realize that there is an opportunity to change or adapt their current behaviors and habits of practice to produce a better result.

The Doing Gap

When there is an awareness that there is something else that can be done to improve the impact of the strategy or skill on student learning, it can often be difficult for educators to use that knowledge to create a new instructional behavior or habit. This inability to do something different is not something that time alone can overcome, but must instead be something we actively pursue through professional development and deliberate practice.

My colleague, Don Marlett, wrote about this idea in his article, “Developing Teacher Expertise – The Obstacle and Opportunity.” In it, he addresses the question, “What makes an expert?” and explores the idea of the Cycle of Improvement and how overcoming what Seth Godin has coined “The Dip,” is an opportunity to improve teacher efficacy.

When teachers miss opportunities in a lesson to improve their implementation, it may be because they are unaware of the continuum of improvement for a particular strategy, skill, or structure. I would argue that this is even truer when the continuum in question is one that is assumed is being used with success.

A Know-Doing Gap Continuum Example: Groupwork

Groupwork… perhaps the most often used collaborative structure seen in classrooms across all grades and content areas.

But if the practice is so often used, why is it often taken for granted that it adds instructional value? After all, students working together means more engagement and active learning, right?

Unfortunately, that is often not the case.

In fact, during my last three school visits, I have walked into multiple classrooms where desks where arranged in clusters of three or four, and the comments from administrators who were accompanying me for the most part focused on the positive: “Thank goodness the rows are gone!” and “Look how the students are on task, even when sitting in groups.”

At no time did someone wonder if all students were equally accountable, or how the groups were tasked with supporting each other’s learning. It was almost assumed that because they were sitting together, they were thinking together. Granted, students sitting together is the technical first step on the continuum of use (you can’t think together if we are not sitting together); I often asked administrators, “How can this teacher improve collaborative learning within the group?” For many this question may be tough to answer; especially because for many educators, our understanding of effective groupwork is limited by our understanding of its continuum.

The Groupwork Continuum

Most teachers began to develop a mental representation of what groupwork should look like from their personal experiences as a student. As students, we were rotated through a myriad of various groupwork structures, such as small group rotations, project-based learning, book circles, and often, just working along in the same space with a small group of students.

While our perceptions of what made these groups effective were limited by our role as the student, we nonetheless frequently remember the groups where we actively learned together, versus just sat together.

Actively learning with and from others requires every groupwork experience to be grounded in the principles of cooperative learning. Also known as positive interdependence, cooperative learning uses a structure to foster equal accountability and collaboration among all students for sharing ideas and knowledge. This helps groups avoid the possibility of being overtaken by one or more students, allowing others to become “free riders,” an all too common outcome of students working in groups.

Structures for Cooperative Learning

Each of the following structures can be used as a structure for groupwork, as each promotes a positive interdependence on learning among students. And while there are many other possible structures for supporting this one aspect of the groupwork continuum, each of these structures is flexible, adaptable, and easy to use in classrooms from all grade levels and content areas.

Jigsaw:

Divide reading into smaller, more manageable chunks by assigning students to a specific topic. Build expertise among students and ensure their interdependence of learning by assigning them to teach their groups.

How Does It Work:

- Groups of students work in a team of four to become experts on one segment of new material, while other “expert teams” in the class work on other segments of new material.

- The class then rearranges, forming new groups that have one member from each expert team.

- The new team members then take turns teaching each other the material on which they are experts.

Tip:

Provide students with a scaffold for discussion. Try sentence starters or a word bank with key vocabulary to help students focus their thinking and promote content-driven discussion.

Placemat Consensus:

Give students a space to independently demonstrate their ideas or knowledge about the topic before summarizing the most important points with a group. Encourages justification through evidence in order to build a consensus among multiple viewpoints.

How Does It Work:

- Pose a question about an important idea, concept, or skill. Each student then takes time to think independently about the question and write their response in their own space on the edge of the placemat.

- When every group member is finished writing, the team shares ideas.

- Once every idea has been shared, the team works together to create one answer with which every member agrees.

- The team then writes this consensus statement or summary in the center of the placemat.

Tip:

Use the strategy as a pre-assessment to see what students know at the start of a lesson, or as a formative assessment to check students’ understanding of important ideas or concepts.

5-3-1:

Assists students with organizing, comparing, contrasting, synthesizing, and sorting information. Students work individually to collect their thoughts and then in small groups to learn through social interaction.

How Does It Work:

- After learning about a topic, reading a selection, or experiencing a learning event instruct each student to write five words about the concept or subject.

- Have students get in groups of three to share their words with each other. The group needs to choose three words from their list that best capture the group’s thoughts about the concept.

- The group then needs to choose one word (from the list of three or a different word) that they decide best fits their understanding of the concept.

- A member of each group should share their word and explain their reasons for choosing it to the class.

- Some students may need more assistance through scaffolding. You can provide a list of words to the students from which they can choose their five words in step one.

Tips:

- Use this strategy with Higher Order Thinking questions that require support with evidence.

- Move away from right/wrong answers by providing students with opportunities to explain their thinking, hear opposing responses, and come to their own conclusions through revolting.

Think-Pair-Square-Share:

Reinforce summarization when partners share their thinking with another pair. Multiple viewpoints allow students to hear different viewpoints and consider any information that might have been overlooked in their original summaries.

How Does It Work:

- Pairs of students are given a question or prompt and then respond on an index card, piece of paper, or whiteboard.

- Pairs share answers and confer about their agreed-upon response, writing it on a response paper or board. Since partners share a response card, they must confer and reach an agreement on an answer and be able to support their reasoning.

- Pairs are squared to form groups of four. Each partnership shares its response board.

- After discussion, all four students are asked to either provide additional information as to why their answer was correct, or they may change their answer and explain why.

Tips:

- Use this strategy with Higher Order Thinking questions that require support with evidence.

- Move away from right/wrong answers by providing students with opportunities to explain their thinking, hear opposing responses, and come to their own conclusions through revolting.

While all of these strategies are sure to improve your students groupwork, there is much more to moving further along the groupwork continuum, including the alignment of the tasks, questions, and prompts with specific standards-driven learning goals, as well as the integration of other high yield, high impact learning strategies, such as distributed summarizing, vocabulary instruction, and writing to raise achievement.

Looking for Instructional Improvement At Your School?

Contact us to learn how we help schools and districts focus on instructional improvement by focusing on addressing The Knowing-Doing Gap represented in instructional continuums.