Beyond Either/Or Literacy Tools: Why Sound Walls AND Word Walls Belong in K-5 Classrooms

May 13, 2025 May 13, 2025

One of my favorite things to discuss with elementary teachers is their classroom environment. Their faces light up with enthusiasm as we chat about furniture arrangements, bulletin boards, and inspirational posters. You can almost see the mental shopping lists forming as they picture their next trip to the dollar store and craft aisles.

During these conversations, I like to ask a question that often sparks rich discussion:

“How might your walls better support literacy instruction, especially in reading and writing?”

That’s the point in the conversation when we discuss two powerful literacy tools: sound walls and word walls. Recently, however, I’ve noticed a concerning trend. As the science of reading gains deserved attention, many teachers feel they must choose between these tools. They ask: “Now that I’m using a sound wall, do I still need my word wall?”

My answer is a resounding yes!. It’s not either/or, it is both/and. These tools serve complementary purposes in a balanced literacy approach, and elementary classrooms benefit tremendously from having both.

The Science Behind the Walls

Research consistently shows that effective literacy instruction requires attention to both decoding (reading) and encoding (writing) processes. According to Dr. Linnea Ehri’s research on orthographic mapping, proficient readers create mental connections between the sounds in spoken words (phonemes), the letters that represent those sounds (graphemes), and the word’s meaning (semantics) (Ehri, 2014).

Sound walls support this mapping process by making phoneme-grapheme relationships explicit and visible. As highlighted in Dr. Mary Dahlgren’s work, sound walls organized by articulation features help students understand how speech sounds are produced, creating stronger neural pathways for reading (Dahlgren & Sánchez, 2020).

Meanwhile, studies on writing development by researchers like Dr. Steve Graham show that easy access to frequently used vocabulary reduces cognitive load during composition, allowing students to focus on expressing their ideas rather than struggling with every spelling (Graham et al., 2018). Word walls address this need by providing visual support for high-frequency and content-specific vocabulary.

By implementing both types of walls, we honor what Timothy Shanahan calls the “reciprocal relationship between reading and writing” (Shanahan, 2016). Each wall strengthens a different aspect of language processing and creates a more robust literacy environment.

Different Tools for Different Literacy Processes

Think of literacy development as two sides of the same coin:

- Sound walls support decoding, helping students break the code of written language. They organize speech sounds with their corresponding spellings, creating a visual map of how language sounds. When a student encounters an unfamiliar word while reading, the sound wall provides a reference point for sounding it out.

- In my observations of effective elementary classrooms, I’ve seen first-graders independently use sound walls during reading practice, pointing to mouth-position pictures to remind themselves how to produce tricky sounds like /th/ or /r/.

- Word walls, on the other hand, support encoding, helping students build words and sentences. They provide readily accessible vocabulary for writing and reinforce spelling patterns, meaning connections, and usage. When students know what they want to say but struggle with how to write it, the word wall becomes their guide.

- I recently watched a third-grade teacher point to her word wall during a writing mini-lesson, reminding students, “If you want to compare two characters, check our comparison words section for ideas.” Students immediately incorporated words like “whereas,” “similar,” and “unlike” into their writing.

Why Memorizing Words Doesn’t Undermine Decoding

The distinction between the two types of wall tools matters, as educators often encounter mixed messages about their purpose and use, especially when it comes to the role of memorization. It’s all too common for teachers to say to me, “We were told that memorizing words will undermine our students’ decoding abilities. Is that true?”

While this is a common concern, it is not backed by research. In fact, there is no credible evidence that memorizing words interferes with or disrupts decoding development. Quite the opposite: multiple studies suggest that, for some students, memorizing words can support the development of decoding skills (Barr, 1974–1975; Biemiller, 1974; MacArthur et al., 2015; MacKay et al., 2022). This makes sense when we consider that English spelling, while complex, is also systematic. It follows rules, even if those rules take time to master.

To be clear, this is not an argument against phonics. Research overwhelmingly supports phonics instruction as a highly effective tool for accelerating early reading development. However, purposeful word memorization can complement phonics when integrated into a well-rounded approach to literacy.

This is especially relevant when we think about word walls. As students are introduced to new words, whether high-frequency, content-specific, or academic, they gradually move into their working vocabulary and eventually into their sight word bank: the words they can recognize instantly and read fluently. But the goal of a word wall isn’t simply to promote memorization. The goal is application. We want students to interact with these words meaningfully, especially during writing, where they can reinforce their understanding of spelling patterns, grammar, and vocabulary use.

Over time, as students encounter more words, English spelling reveals its underlying logic. When students learn to recognize words by sight, particularly irregular or high-utility words, they begin noticing consistent sound-letter patterns. In this way, sight word learning moves beyond rote memorization and becomes an exercise in structural recognition and pattern building (Ehri, 1995; Ehri, 2009; Ehri, 2020; Wright & Ehri, 2007).

Research backs this evolution. As decoding skills develop, memorizing words becomes easier—not because students rely solely on visual memory, but because they’re beginning to internalize spelling-sound relationships and identify familiar orthographic patterns (Levy & Lysynchuk, 1997). Through systematic phonics instruction or independent exploration, students increasingly learn words as part of a meaningful and predictable system.

This transition, from memorization to meaningful use, is critical. It reflects a deeper literacy level where students aren’t just recalling words, but applying them to express ideas, analyze texts, and communicate effectively. That’s the real power of a word wall: not as a static display, but as an active tool that highlights spelling patterns, reinforces encoding, and supports writing fluency.

Ultimately, you don’t need to choose between phonics and memorization. The most effective literacy instruction integrates both. Used thoughtfully, word walls become more than a collection of terms; they become a bridge between decoding and writing, recognition and expression, and memorization and application.

Building Word Walls

As students progress through the grade levels, the structure and purpose of word walls should evolve to meet their growing needs. It is essential to note that there are varying types of word walls, each serving a different purpose in supporting literacy development.

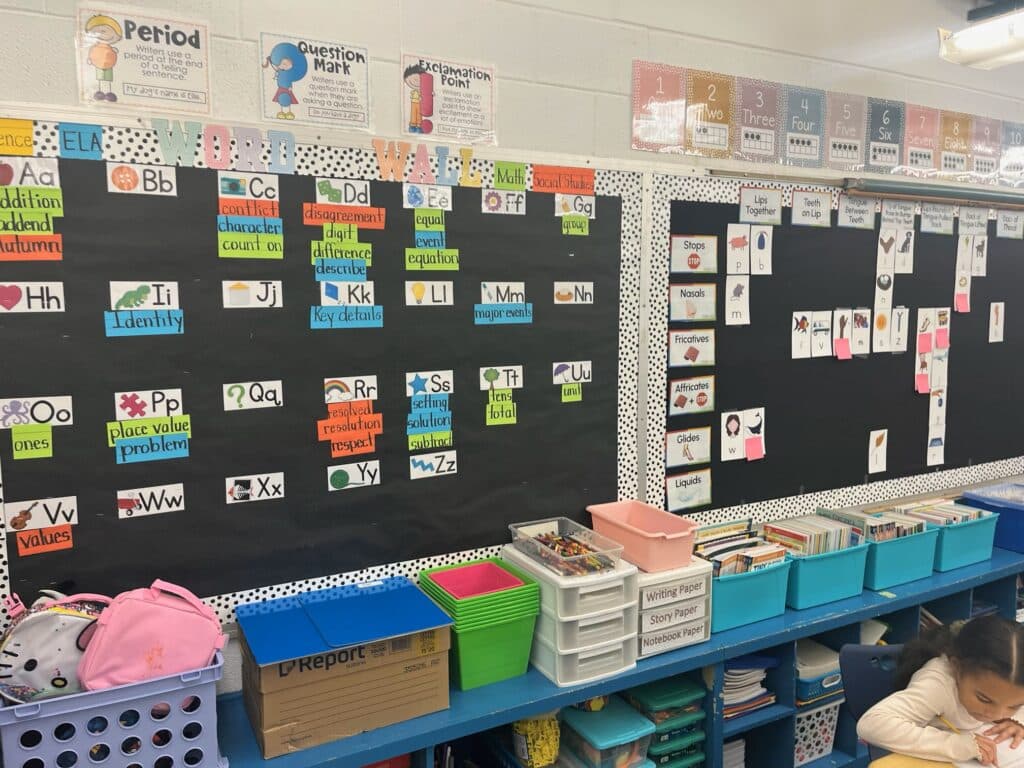

In K–2 classrooms, word walls are typically organized alphabetically to help students internalize high-frequency words and reinforce letter-sound associations. In the picture below, the teacher has included both content-specific vocabulary, such as president and citizen, and academic vocabulary like important and perspective. This combination ensures students build foundational decoding skills while expanding the vocabulary needed for comprehension and writing. Alphabetical organization supports early phonics instruction by reinforcing letter-sound correspondence. At the same time, the inclusion of meaningful vocabulary introduces students to the types of words they will encounter in texts and be expected to use in their writing. This dual focus lays a strong foundation for their more advanced literacy tasks in later grades.

However, as students move into grades 3–5, the focus shifts from simple word recognition to understanding how words relate to one another to build meaning. At this stage, the word wall should reflect that shift through conceptual or thematic organization.

For example, I recently collaborated with a 4th-grade math teacher to rethink her word wall. The original setup listed vocabulary alphabetically, and we retained this format for general academic terms like compare, conclude, and justify to support quick access. However, we restructured content-specific terms using semantic groupings—for instance, clustering dividend, divisor, and quotient. This helped students see how these terms work together within the division process, deepening their understanding and improving their ability to apply the vocabulary during math problem solving and writing.

This approach, organizing vocabulary into conceptual groups, becomes increasingly important after second grade. Rather than presenting words as isolated units, semantic groupings encourage students to analyze relationships and build mental frameworks that support comprehension and academic discourse. For example, grouping terms representing parts of a process, like dividend, divisor, and quotient, helps students understand the definitions and the roles these terms play in context.

Examples and Activities: How to Use Both Word Walls and Sound Walls in Your Elementary Classroom

Early in my teaching career, I used to think word walls were alphabetized lists of vocabulary words we’d occasionally reference. In my second year of teaching, I created an ambitious word wall crammed with vocabulary and high-frequency words. We played review games with it occasionally, and I pointed to it now and then. But I wasn’t using it as a consistent, purposeful tool to support my students’ writing.

Over time, and through conversations with many teachers, I’ve come to see that the real value of a word wall depends entirely on how it is used. While sound walls are designed to support decoding by making phoneme-grapheme connections visible, word walls are most powerful when they actively support encoding, helping students build sentences, apply vocabulary, and develop writing fluency.

Activities With Sound Walls:

- Daily Sound Practice: Begin each phonics lesson by referring to the sound wall, having students locate and practice the target phoneme. Research from the National Reading Panel emphasizes that explicit, systematic phonics instruction is most effective when it includes regular review (NICHD, 2000).

- Sound Sorts: Give small groups cards with pictures or words and have them place each card near the corresponding phoneme on the sound wall. This reinforces phonemic awareness while creating muscle memory for locating sounds.

- Reading Application: When students encounter an unfamiliar word during reading, teach them to look at the sound wall to identify the phonemes and blend them together. One kindergarten teacher I observed has students “tap out” the sounds on their fingers while looking at the wall.

- Word Building: Use the sound wall as a reference during encoding activities. For example, during interactive writing, ask, “What sound do you hear at the beginning of ‘ship’? Where can we find that sound on our wall?”

- Sound Detectives: Challenge students to find objects in the classroom whose names contain target sounds, then add pictures of these objects to the sound wall. This builds ownership and engagement.

Activities With Word Walls:

- Word Collecting: Have students become “word detectives” who collect interesting or useful words from their reading to add to the word wall. Research by Beck, McKeown, and Kucan suggests that this active involvement increases word learning (Beck et al., 2013).

- Writing Conferences: During writing conferences, explicitly reference the word wall: “I notice you’re comparing these two characters. What words from our comparison section might make your thinking clearer?”

- Word Wall Scavenger Hunts: Give students categories (e.g., “Find three words that help sequence events”) and have them locate words on the wall that match. This reinforces both the location and function of words.

- Sentence Building: Provide sentence frames with blanks where word wall vocabulary could fit: “The rabbit hopped _______ the garden.” Have students choose appropriate words from the wall (through, across, around) to complete the sentence.

- Word Wall Tours: When introducing new students to the classroom, have existing students give a “tour” of the word wall, explaining how it’s organized and when they use it. This reinforces student ownership and usage.

Making Both Walls Work in Limited Space

Many teachers worry about classroom real estate. Where do both walls fit? Here are some space-saving solutions:

- Integrated Displays: Some teachers effectively combine both walls by creating a sound-to-word connection, such as hanging high-frequency words near the phonemes they predominantly use.

- Portable Walls: Create mini-versions of both walls that students keep in their writing folders or reading notebooks.

- Rotating Displays: Focus on the most words for instruction. Not everything needs to be visible all the time.

- Vertical Space: Use hanging pocket charts or behind-the-door space to maximize wall usage without sacrificing prime instructional areas.

From Static Display to Dynamic Tool: 4 Wall Characteristics

What distinguishes truly effective literacy walls from simple classroom décor is how intentionally they are used. To serve their full purpose, both walls should be:

- Interactive: Students should reference and actively use the wall during learning.

- Evolving: The content should shift over time to reflect ongoing instruction and student growth.

- Accessible: Walls should be a visible, usable part of daily learning.

- Purposeful: Every word or concept displayed should align with current instruction and support specific learning goals.

Maximizing the impact of word walls in upper elementary grades depends on regular student interaction. Students should feel encouraged to use the wall as a resource during small-group instruction, independent tasks, or writing blocks. To extend this support, consider creating mini or portable word walls that live at desks or learning stations, allowing students to access key vocabulary throughout the day.

For example, I recently saw a 5th-grade ELA teacher pose the lesson essential question: How do characters’ actions reveal the theme of a story? She asked pairs to use two to three words from the word wall in a partner discussion to predict a possible answer, such as motivation, theme, conflict, or evidence. As students talked, many stood up to refer to the wall and incorporated the academic vocabulary into their responses, saying things like, “The character’s motivation was to protect his family, and that shows the theme of loyalty.” This vocabulary scaffolding helped students express more precise, analytical thinking and supported their writing later in the lesson.

By transforming word walls from static, alphabetized displays into conceptually organized, interactive literacy tools, we support more than word recognition, we cultivate vocabulary depth, writing fluency, and conceptual understanding. These dynamic tools help students internalize academic language and apply it purposefully in reading, writing, and thinking.

3 Common Questions from Elementary Teachers

- “I’m required to use a commercial sound wall program. Can I still create my own word wall?” Absolutely! Commercial programs provide excellent structure for sound walls, but you can complement this with a custom word wall that reflects your specific curriculum and students’ needs.

- “When should I introduce each wall?” Many teachers introduce the sound wall structure at the beginning of the year, then gradually add phonemes as they’re taught. Start with a small core of high-frequency words for word walls, then add categories and vocabulary as your writing instruction expands.

- “How do I assess whether my walls are working?” Watch for student independence. Do they reference the walls without prompting during reading and writing? Can they explain to others how to use the walls? Do they suggest words to add? These behaviors indicate the walls have become true learning tools.

Building Bridges, Not Choosing Sides in Literacy Development

The debate between sound and word walls often mirrors broader tensions in literacy instruction. However, effective teachers know that comprehensive literacy development requires attention to both decoding and encoding processes.

Sound walls help students hear and decode language. Word walls help them write and apply words. Together, they form a bridge between reading and writing, a bridge that elementary students cross countless times each day as they develop into confident, capable readers and writers.

So when planning your classroom environment, remember: it’s not about choosing between sound and word walls. It’s about creating a space where both tools work together—where every wall serves a purpose, and every purpose serves your students’ growth as readers and writers.

Because ultimately, the most important thing on our classroom walls isn’t the perfectly laminated cards or color-coded categories. It’s the evidence that students are using these tools, the fingerprints, the additions, the wear-and-tear that shows these aren’t just displays.

Effective literacy walls make for effective co-teachers!

References:

Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2013). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. Guilford Press.

Dahlgren, M. E., & Sánchez, K. S. (2020). When reading gets ruff: Understanding the literacy experiences of children engaged in a canine-assisted reading program. Reading Improvement, 57(1), 35-47.

Ehri, L. C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(1), 5-21.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Santangelo, T. (2018). Writing expertise. In D. S. Busso & F. K. Mareschal (Eds.), Handbook of expertise: Development, language, and decision making (pp. ix, 359). Cambridge University Press.

National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Shanahan, T. (2016). Relationships between reading and writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 194-207). Guilford Press.