Key Points:

- More powerful than bulletin boards, a Writing Wall showcases student writing across all grades and subjects—sending a clear message: writing matters.

- Start with one wall, one grade, or one subject. Invite colleagues to join you. Share what works and what you’re still figuring out.

- Writing-to-learn strategies boost comprehension and retention—and Writing Walls make that learning visible, reinforcing growth schoolwide.

- For leaders, Writing Walls are more than a celebration; they’re professional learning tools and a visible signal of schoolwide priorities.

- Writing Walls thrive when schools set clear routines for contributions, updates, and student representation—without them, walls risk becoming static displays.

- Process over perfection: great Writing Walls show thinking in progress—organizers, drafts, and reflections—not just polished final pieces.

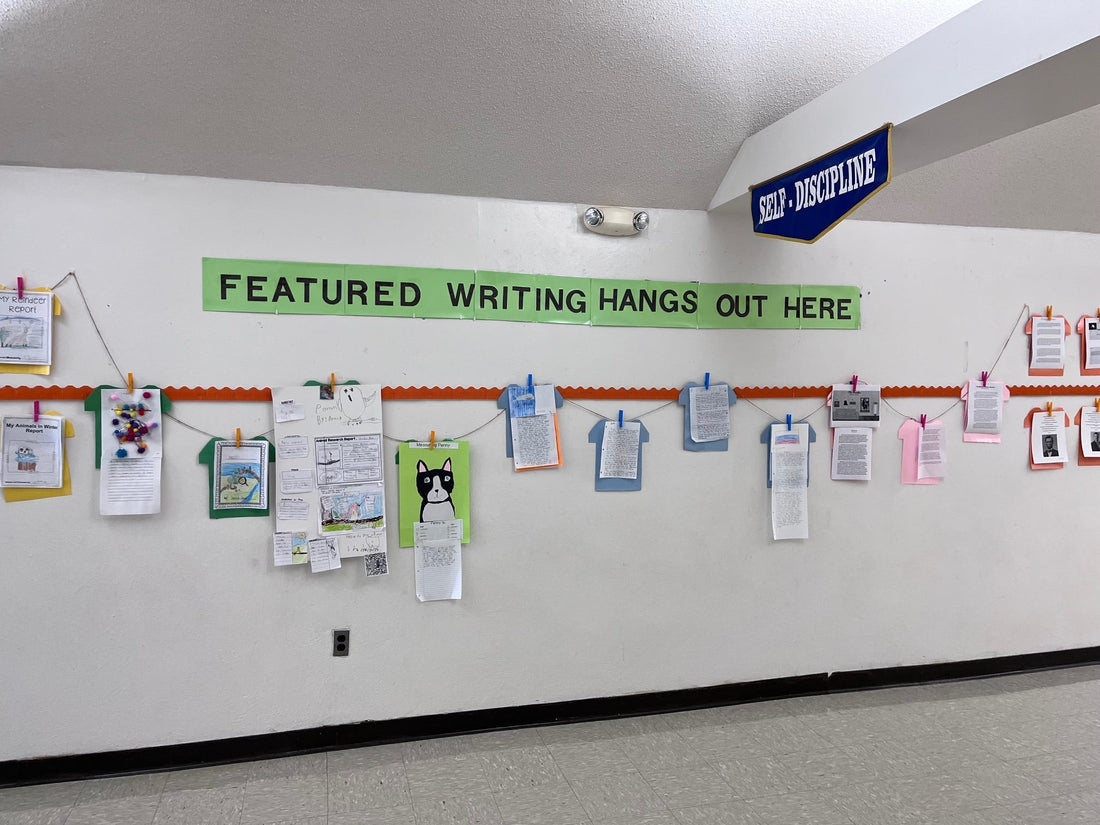

Walk through a school that celebrates writing, and you’ll feel it right away. The hallways talk. Student words line the walls, not as filler or decoration, but as evidence that every learner has something important to say. That's the heart of a Writing Wall.

What Is a Writing Wall?

As the name implies, a writing wall is a dedicated space where schools showcase student writing from every grade level and content area. More than a bulletin board, it’s a message: writing matters here. And it's powerful for a multitude of reasons.

Why Writing Walls Make a Difference

The true power of a Writing Wall lies in its visibility. When writing is displayed, it transforms from a private assignment into a public celebration of learning. Visibility is the spark that promotes reflection, fuels collaboration, and drives motivation across the school.

For students, this visibility means their voices are heard and their efforts recognized. A once-private piece of writing now becomes a source of pride and validation. For teachers, Writing Walls provide a window into strategies and progress across grade levels, sparking collaboration and shared learning. For the entire community, families, peers, and administrators, they stand as living evidence of growth and achievement.

-

Motivation for students: “My writing matters enough to be on the wall.”

-

Collaboration for teachers: “How did you teach that structure? Let’s try it.”

-

Evidence of growth: The wall becomes a living portfolio of the school’s writing journey.

The simple act of making writing public turns hallways into classrooms, invites collaboration among educators, and reminds students that their words matter far beyond a grade.

The Research Behind Writing Walls

This visibility isn’t just powerful in practice; it’s powerful in research. Studies show that writing-to-learn practices deepen comprehension and retention by requiring students to organize, clarify, and communicate their ideas (Graham & Hebert, 2010). When that process is made visible through Writing Walls, the learning doesn’t stop at the page, it becomes part of the collective growth of the school.

This echoes the findings of the National Commission on Writing (2003), which argued that writing is not just a communication skill but a central tool for learning across the curriculum. More recently, reviews confirm that embedding writing into all content areas significantly boosts comprehension and achievement, reinforcing the importance of schoolwide practices like Writing Walls (Colorín Colorado, 2024).

In short, the research confirms what educators see every day: when student writing is visible, it strengthens both learning and community. Writing Walls make that learning public, purposeful, and powerful.

What Belongs on a Writing Wall?

Educators often ask: What should actually go on the wall? While the essential part of the Writing Wall is to display student work, it can be elevated when schools decide to highlight both the process and the final product.

This attention to capturing the entire process ensures that anyone walking by, students, parents, teachers, administrators, sees not just the finished writing, but also the thinking and effort behind it.

Including all of the following isn’t required, but each component adds value:

-

Standards clarify what skills the writing demonstrates and communicate expectations across grade levels.

-

Lesson Essential Question anchors the purpose and connects the writing to the unit’s big ideas.

-

Graphic Organizer shows how students organized ideas before drafting.

-

Draft may be included to show revision in action, but schools can adjust based on space, age group, or teacher preference. Even one highlighted example of revision can help reinforce that writing improves with effort.

-

Final Piece highlights polished student work and celebrates achievement, showing students their effort pays off.

-

Reflection gives students a voice in evaluating their own growth.

-

Feedback can be posted to celebrate progress, for example, teacher comments or peer praise that highlight growth.

-

Privacy Note: To protect student identity, schools may choose to remove names or display first names/initials only. This ensures the focus remains on the learning while still celebrating achievement.

Building the Routine: Roles, Rotation, and Representation

For Writing Walls to have a lasting impact, schools need clear routines for who contributes, how often walls are updated, and how students are represented. Without shared expectations, walls risk fading into a “one-time display” rather than becoming a living celebration of writing.

Who Makes the Wall?

There are two common approaches:

-

Teacher-Led: Each teacher is responsible for selecting and submitting a piece from their class, with rotations scheduled every 2–4 weeks. This ensures a steady flow of new writing and places ownership in the hands of classroom educators.

-

Principal-Led: The principal or instructional leader oversees the wall, collecting pieces from each grade level and coordinating updates. This model signals that writing is a schoolwide priority championed at the leadership level.

Either approach can work, but what matters most is consistency. Writing Walls thrive when teachers and administrators share the responsibility, rather than leaving it to chance.

Student Selection

Equity is key. A Writing Wall of Fame should represent all voices, not just the “best” writers. Many schools adopt the expectation that every student must be represented before any student is repeated. This builds confidence across the student body and avoids the perception that the wall is reserved for a select few.

Update Frequency

Walls should feel alive, not static. Refreshing the display every 2–4 weeks keeps student work current and gives families, teachers, and peers something new to engage with regularly. A predictable update cycle also allows teachers to plan writing assignments with the wall in mind.

Why It Matters

When routines for updating, selecting, and celebrating student writing are clear, Writing Walls become more than décor; they become a rhythm of school life. Students know their turn will come. Teachers know their work will be highlighted. Principals know the wall will reflect ongoing growth, not a single moment in time.

Teachers: Making the Wall Work

Writing Walls don’t create impact on their own. Their value comes from the way teachers design, curate, and use them to spotlight student thinking. The strongest displays show not just a polished final draft, but the process and structure that led to it.

Research on classroom practice underscores this point: giving students frequent, structured opportunities to write across subjects not only improves their writing, but it also strengthens their comprehension and retention of content. Writing-to-learn strategies, like those showcased on Writing Walls, help students clarify their thinking and make learning visible (Graham & Hebert, 2010).

Across Grade Bands

Grades K–2

- Post organizers like “beginning, middle, end” alongside finished pieces.

- Celebrate growth—even inventive spelling shows progress.

- Display student drawings with emerging writing to honor early literacy.

-

Add a student quote about their piece: “I worked hard to make my ending funny!”

Grades 3–5

- Feature text structures (cause/effect, compare/contrast) with color-coded highlights.

- Use the wall in class: “Let’s look at how a 4th grader explained their evidence.”

- Invite students to give “wall tours” explaining their writing process.

- Rotate writing across subjects, science reports, social studies journals, and math explanations.

Grades 6–12

- Showcase cross-curricular writing: Document-Based Questions (DBQs), lab reports, argument essays.

- Post annotated exemplars (“Here’s the thesis; notice how evidence is cited”).

- Invite students to do gallery walks and pull strategies to use in their own work.

- Encourage students to submit a short author’s note with their piece, explaining their writing choices or challenges they overcame. This deepens reflection and helps peers see writing as a process, not just a product.

Administrators: Leading with Writing Walls

For leaders, Writing Walls are more than a celebration; they’re professional learning tools and a visible signal of schoolwide priorities.

- Use them on learning walks: Pause with teams to ask, “What text structures are visible? What skills are students practicing?” Connect what you see to instructional priorities.

- Bring them into PLCs: Select samples to score together, compare rubrics, or identify next steps for instruction.

- Spot vertical alignment: Use the wall as a quick visual to ask, “How do expectations shift across grades? Where are the gaps?”

- Celebrate teachers: Publicly recognize staff who contribute powerful student samples, both in meetings and newsletters.

- Link to school goals: Connect the Writing Wall to larger improvement efforts (e.g., literacy across the curriculum, nonfiction writing emphasis).

- Engage families and community: Encourage parents, board members, or visitors to walk the wall during open houses or events.

- Create feedback loops: Ask students and teachers what they notice when they look at the wall. This builds ownership and makes the wall a living conversation, not just a display.

Research shows these leadership moves are more than symbolic. Shanahan and Shanahan (2008) found that when schools deliberately cultivate writing across subjects, achievement rises not only in ELA but also in content areas like science, social studies, and math.

“When schools develop a culture of writing across disciplines, student achievement increases not just in ELA, but in content areas where writing clarifies and deepens learning.” —Shanahan & Shanahan (2008)

Guiding Questions for Learning Walks and PLCs

When stopping at a Writing Wall, administrators and teacher teams might ask:

- Process and Structures

- What text structures (e.g., cause/effect, argument, narrative) are evident?

- How is the writing process (organizer → draft → final) represented?

- Standards and Alignment

- Which writing or content standards does this sample address?

- How do expectations shift across grade levels?

- Where do we see consistency, or gaps, in vertical alignment?

- Student Thinking

- What does this sample reveal about how students are reasoning, organizing, or using evidence?

- How are students showing growth over time?

- Instructional Moves

- What strategies might have supported this writing?

- How could teachers across content areas use similar approaches?

- Celebration and Feedback

- How can we highlight both student effort and teacher impact here?

- What affirmations or next steps could be shared in PLCs or coaching conversations?

Walls aren’t just about showcasing student work; they serve as a window into the school’s instructional priorities. Administrators who engage with those walls turn displays into professional learning opportunities.

Getting Starting

From One Educator to Another

A Writing Wall of Fame is more than a display board or a bulletin board; it’s a statement. When student words take center stage, schools build a culture where writing belongs to everyone, everywhere.

A principal I recently worked with summed it up best:

“Our hallways started talking. Students stopped to read, compare, and point. Teachers started asking each other, ‘How did you teach that structure?’ Writing became everyone’s business.”

Writing reminds us that growth happens through drafting, revising, and trying again. Teaching is no different. Every time we take a risk in our instruction, we model for students the very process they practice in their writing. Writing Walls give us a chance to celebrate those risks and revisions, both students’ and teachers’, as visible reminders that success is built step by step, word by word, revision by revision.

So start with one wall, one grade, or one subject. Invite colleagues to join you. Share what works and what you’re still figuring out. Together, let’s create spaces that celebrate courage, honor growth, and remind every learner that writing and teaching are processes worth sharing.

References

- Colorín Colorado. (2024). Teaching writing in the content areas: Research to practice. Author.

- Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

- National Commission on Writing. (2003). The neglected “R”: The need for a writing revolution. College Entrance Examination Board.

- Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40–59. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101